Thoughts on Restructuring Classical Music: The Aesthetic and Ethical Implications of Altering Canonical Masterworks

The application of Extreme Transcription to classical music masterworks has sparked significant debate. While some argue that altering these compositions compromises their perfection and the composer’s original intentions, others assert that sharing the classical music canon in any form is justifiable if it moves audiences emotionally.

This debate raises both aesthetic and ethical questions: Should these works be preserved unchanged as monuments to their creators, or is reinterpretation a necessary step to ensure their relevance to contemporary audiences? The answers remain elusive, and the ultimate judgment may rest with time and the responses of listeners worldwide.

Below is a series of essays drawn from a multi-year research project on orchestral transcription that explore these issues in depth.

1. Introduction

2. Authenticity and Aesthetics in Transcription

3. How Technology Facilitates the Aesthetics of Transcription

4. The Ethics of Music Attribution

5. Works and Versions

6. Purism and the Ethics of Transcription

7. On Being Faithful

References

Footnotes

1. Introduction

While many forms of American music have arisen and developed, the classical music tradition brought over by European immigrants has remained relatively static. The vehicle primarily used for performing classical music – the symphony orchestra – remained fixed in size, instrumental configuration and repertoire.

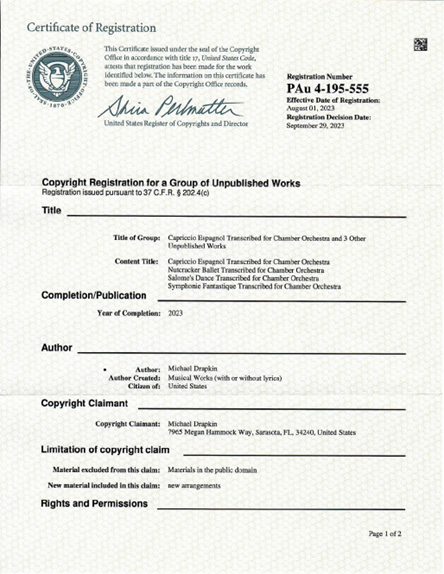

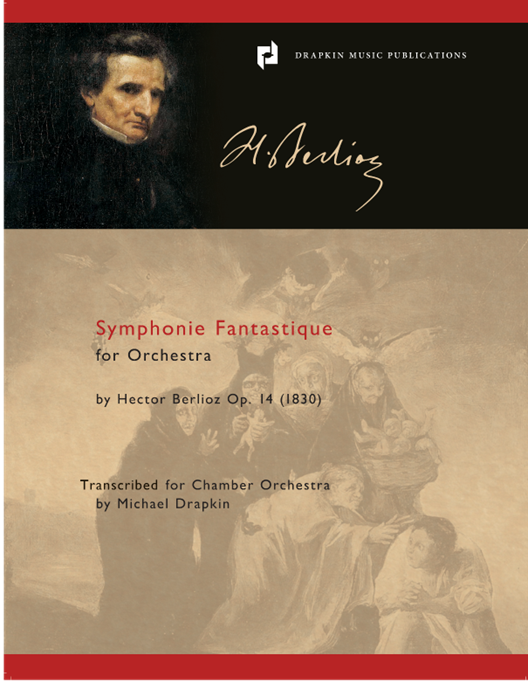

This discussion advocates for several changes in the modus operandi for orchestras, detailed in the book Extreme Transcription Chapter 2: Extreme Transcription Techniques, which advocates and enumerates the techniques that I have developed to transcribe full symphonic works for use by chamber orchestras. It is Extreme Transcription which is the impetus for this section: an examination of the aesthetic, ethical, and relational issues associated with taking existing musical works and transcribing them for a different sized ensemble.

Transcribing orchestral works, or any music for that matter, is a fait accompli. Music has been transcribed or arranged into myriad forms across a variety of media. I draw a distinction between arranging, where works or tunes can be put in settings in an infinite number of ways, and transcribing, where the goal is to take a symphonic work and modify it so that it can be performed by a chamber orchestra in a manner that is as close to the original as possible.

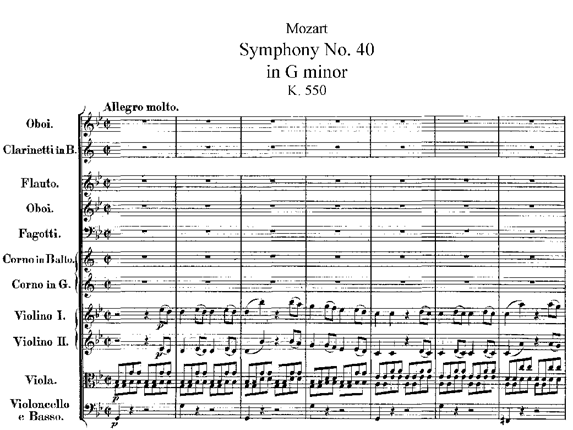

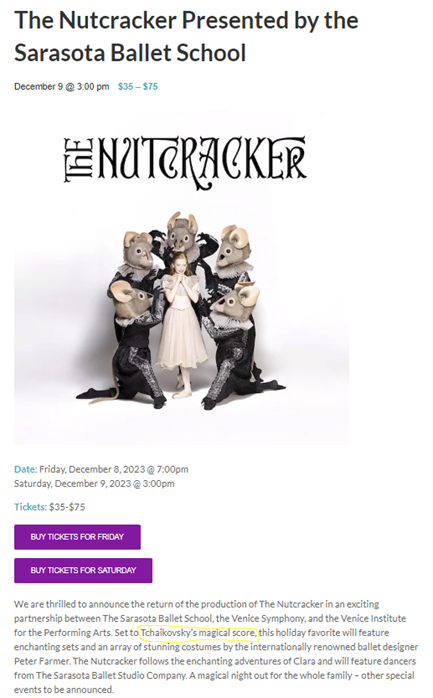

One can go in the elevator and hear a melody from Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite (Op. 71a, 1892), and it will probably not be in the original orchestration. One might also hear an arrangement of a song by the Beatles, played by strings but still recognizable as a Beatles song. Even J.S. Bach “did not hesitate to make double use of originally secular works by adapting them to sacred texts, or to include movements from concertos and other instrumental compositions in his cantatas.” (David and Mendel 1966: 33) The repurposing of compositions by composers like Bach was and is not unusual. Tchaikovsky released his Nutcracker Ballet (Op. 71, 1892) and his Nutcracker Suite at the same time. What is unusual, and bears examination, is when third parties, such as me, take it upon themselves to transcribe an existing work and evoke a sameness making a difference

In other words, there are implications to making changes to classical music works through the techniques examined in the Extreme Transcription book. There would likely be fewer implications if one were merely arranging music from these works or just using their melodies, given that the goals and restrictions associated with arranging are usually different from those argued for here. I call for these works to be transcribed in their entirety for a smaller ensemble, and then presented as the same work in a chamber orchestra concert instead of the original symphony orchestra format. In other words, the transcribed version for chamber orchestra presents Strauss’s Salome’s Dance in concert as the same work, albeit with a caveat under the composer’s name: “Transcribed for Chamber Orchestra by Michael Drapkin,” for example.

But the two versions are not the same, and that also leads to two opposing standpoints. Some argue against changing something that is already perfect and was the composer’s intention when they composed the work, although we cannot be sure what that intention was. Others aver that the sharing of the classical music canon in any form is justifiable if it allows current and future audiences the ability to enjoy these works and hear them live in performance.

Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker Ballet provides a notable example of the difficulties that arise when making changes to a work, even when it is done by the original composer. His Nutcracker Suite allows eight of the numbers from the ballet score to be performed by a symphony orchestra in a concert setting and to be shared with greater audiences. However, in doing so, only one of the three waltzes that he composed for the ballet, the “Waltz of the Flowers,” is included in the suite, even though there are two more waltzes that – I would argue – are of equal stature to the single waltz that Tchaikovsky included in his suite. This means that The Nutcracker Suite audiences will not be able to listen to all of the music unless they go to a performance of the full ballet .

Given the cost of hiring an entire professional full symphony orchestra to perform The Nutcracker with a ballet company, one still runs the risk that the ballet company may use one of the many reduced versions of the ballet score, or even play back recorded music with no live orchestra at all. In both cases there is still music heard with the ballet performance, although it is possible the ballet company may also decide to make cuts to the music.

Each one of these versions result in an enormous number of changes to the original score, especially when you consider that the ballet score is 511 pages long. Therefore, with a nod to Gregory Bateson’s phrase “a difference that makes a difference” like a pebble hitting a flat pond surface causing it to ripple, in this case it is “a sameness that makes a difference.” (Bateson 1971: 231) The changed versions are still materializations of The Nutcracker, but also rendered into something different.

What is the right thing to do? Full ballet or suite, full orchestra or reduction, live performance or recorded music, and full score or score with cuts? In all of these permutations, the audience gets to enjoy Tchaikovsky’s music, but whether it is the “right thing to do” is still a gray area and that is the point of this chapter. It explores thoughts about the ethics and aesthetics of “the sameness making a difference” to classical music works from a number of different perspectives and viewpoints, in light of what others in the larger musical and philosophical community have had to say about aspects of this subject.

Authenticity and Aesthetics in Transcription explores the relationship between original and transcribed works: How do issues of aesthetics, authenticity and the nature of transcription fit into the understanding of that relationship? How Technology Facilitates the Aesthetics of Transcription looks at the ethical issues that arise when examining how technology has changed the processes by which music is produced. The Ethics of Music Attribution looks at the ethics of authorship that can occur when trying to understand the attribution of credit to those who contribute to a work. Works and Versions examines how to categorize musical works that are very similar, and whether a transcription is a version of the work on which it is based or whether it is the same work. Purism and the Ethics of Transcription examines the ethical issue of whether transcription should be done at all and compares this against historical practices. Finally, On Being Faithful examines whether canonical works can or should be transcribed and whether and how these transcribed versions should still remain faithful to the work on which they are based.

As mentioned above, transcription and arranging can take on many different forms, from the “sameness” sought in transcription, to a remix, where the original is changed or twisted by removing, adding or otherwise modifying parts of the composition. As a wind player, I started playing music that was originally written in other forms the minute I set foot in a concert band. When I was 13 years old, my first band concert had a medley of tunes that were written originally for jazz band and for Broadway shows. In high school, I performed a concert band transcription of the last movement (Allegro non troppo) of Symphony No. 5 by Dmitri Shostakovich (Op. 47, 1937), “Elsa’s Procession to the Cathedral” from Act 2, Scene 4 of the opera Lohengrin by Richard Wagner (WWV 75, 1850) and many other works. The first tune I recall in my beginning clarinet method book started with an arrangement of the German folk song “Hänschen Klein” – Lightly Row. When I attended the Eastman School of Music and played in the Eastman Wind Ensemble, we performed a band transcription of Ottorino Respighi’s bombastic orchestral piece Feste Romaine (P 157, 1928). Certainly, as wind players, we have been surrounded by transcriptions and arrangements from the earliest formative moments of our musical experiences and that has been the norm. Hence, I have not thought twice about the idea of transcribing a work, unless there were copyright issues involved.

We are so buffeted by multiple kinds of media in today’s society that we are inured as to its original source or format. You could be walking down the street and hear music playing in a store, or during an advertisement on television, or something on the computer, tablet, phone or web browser. I often watch a show on TV and recognize an excerpt from Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet (K 581, 1789) – a work I have performed numerous times – or a cantankerous piece by Sergei Prokofiev, depending on the setting and/or mood that the film composer wants to elicit (or to avoid having to pay licensing fees if the piece is in the public domain). Therefore, this chapter will not concern itself with whether this practice exists – it is ubiquitous – but rather with what it means and how it fits into our understanding of the practice of transcription as advocated here and demonstrated on this website.

Provided here is an attempt at a justification for the transcribing done of symphonic works to chamber orchestra as part of the argument that the focus in America on professional symphony orchestras needs to shift to the use of professional chamber orchestras in specific communities. Philosopher Lydia Goehr’s first book, The Imaginary Museum of Musical Works, which was published in 1992, goes into the idea of musical works, and the historical, philosophical, and musical questions that define them. This tracks closely to many of the questions that I address in examining the ethics and aesthetics of transcription, hence I often will quote Goehr in this chapter. She pointed out that in Weber’s time “…composers believed that they should be able to live and function as free individuals, and that their productive activities should, if they should be subject to anything at all, be subject to the forces of an urban market for music.” (Goehr 2002: 207) Transcribing symphonic music from the classical music canon for chamber orchestra also reflects what the markets for this music dictate. However, it also opens up questions of ethics and aesthetics with respect to transcribing canonical orchestral works.

Musicologist and philosopher Peter Kivy’s 1995 book Authenticities describes and reflects on four different manifestations of authenticity in musical performance. The first, “The Authority of Intention,” examines composers’ intentions, and performers following or not following what they believe that to be. The second, “The Authority of Sound,” looks at sonic authenticity with respect to what might be the composers’ intention for what a work should sound like when performed and the issue of what is sensible given the time, instruments, and performance practices of the day. The third, “The Authority of Practice,” looks at how the concept of aesthetics changed with the invention of the modern concert hall, which focused the listener on the details of the performed work, particularly since prior to circa 1800, music was performed not as the center of listener attention, but alongside other activities that were taking place socially.

It is the last one, “The Other Authority” (personal authenticity), that bears careful examination in the context of transcribing works from the classical music canon. The act of transcribing entire works by Berlioz, Rimsky-Korsakov and Strauss weighed heavily upon me when I chose to create new versions of those same works for chamber orchestra, as pointed out above. I would go as far as suggesting that Kivy’s authenticities need a fifth one, “The Authenticity of Transcription,” which will be examined later in this chapter. I grappled with a number of soul searching questions before I began the transcription process: Do I have the requisite skills to create excellence in my transcribed works? Did I pick works that are conducive to being transcribed, or am I setting myself up for failure? Do I believe that I can imbue my transcribed works with what I believe to be the compositional and aesthetic essences of what these great masters of composition created many years ago, some of which to me border on magic? How will others judge what I create?

Kivy applies the concept of personal authenticity to how performing artists interpret or bring out the expressive qualities of a musical work. This is no different than how I as a performer may personally interpret and create a musical performance. That same professional and personal performing ethic was applied to the transcription process, so the questions that I ask myself about transcribing in the previous paragraph are very similar to those I invariably have when I choose to learn and perform a challenging work of music as a performer. When I create a transcription, I am not necessarily a performing artist but still applying the same desire: if I were to perform the principal clarinet part to Capriccio Espagnol, which features clarinet solos and even a cadenza, I’d want to do justice – technically, artistically and expressively – to Rimsky-Korsakov’s work. Similarly, when I transcribe it, I want to do the same thing. However, when I transcribe works, the pressure to do justice is magnified manyfold since I take it upon myself – as the transcriber – to interpret the original composer’s entire composition and orchestration – not just the clarinet part. When transcribing, the goal is to create something that not only technically recreates what I believe comprises the original composition in a chamber orchestra setting, but that also maintains the same opportunities for the performing artists to express themselves as they would in the original orchestration: authenticity as transcriber.

Both, to me, are instances of Damocles sword being held over one’s head: the performing artist is judged by the personal authenticity of their performance, and I am judged by my ability to be personally authentic in my transcribed works, and both are judged when the transcribed music is performed, even though I may have written my score months, years or even decades before. Therefore, this heady responsibility is not taken at all lightly. I experience the same “butterflies” or performance anticipation before I perform a solo as I do when I open the original score of a work that I want to transcribe. When my transcribed works were being recorded in Ostrava, I also experienced the same butterflies on the floor of the recording studio before the first note of my transcribed works were played by the orchestra, and I had the same feeling of relief when it was over. In conclusion, the book Extreme Transcription” outlines the “how,” and these essays explore the “why.”

2. Authenticity and Aesthetics in Transcription

When I was living in New York City, I had a friend working on her master’s degree in fine arts from Columbia University – a painter. One day she asked me if music performers were artists, since they don’t create the music but merely recreate what the composer has created. Therefore, according to her, performers weren’t artists. This caught me by surprise, and I have mused over that conversation since then. I responded that when it comes to the performing arts, the composer and their work don’t exist without the performer in the same way as a performer doesn’t exist without something to perform. Plus, it is the performer that takes what the composer has written on the page, interprets it, and communicates it to the audience. Without the performance and the performer, what the composer writes is just paper with symbols on it.

Wynton Marsalis said almost the same thing as my painter friend, just from his perspective: “Concert musicians are artisans – jazz musicians are artists. . . . With Bach or Haydn, you know what you’re playing is worth hearing, and the best thing you can do is not mess it up. In jazz, you have to have something worth saying and then know how to say it” (Buschel 1987). This is a bit chauvinistic from a genre standpoint, but it does reinforce my friend’s question about what constitutes an artist, and these issues will both be addressed below.

In his book Art Worlds, published in 1982, sociologist Howard S. Becker looks at the relationships between musicians, dealers, critics, suppliers, and consumers, as well as the artist, that converge to create a work of art. Becker applies these relationships to the symphony orchestra:

For a symphony orchestra to give a concert, for instance, instruments must have been invented, manufactured, and maintained, a notation must have been devised and music composed using that notation, people must have learned to play the notated notes on the instruments, times and places for rehearsal must have been provided, ads for the concert must have been placed, publicity must have been arranged and tickets sold, and an audience capable of listening to and in some way understanding and responding to the performance must have been recruited. (Becker 1982: 2)

Becker’s description is a good inventory of the human and nonhuman components needed to stage a symphony orchestra concert. However, it does not include the personal aesthetic that one expects when attending a concert. The attendees are not there to hear a reproduction by artisans, as Marsalis puts it, otherwise they could just download a recording from iTunes. To me, being a performer is much more than just mechanically reproducing something on a printed page. Performers are not just expected to have the technical facility needed in order to accurately play what is on their sheet music (and this includes the ability to play the notes, articulation and dynamic range). It also includes producing a good tonal quality, the ability to follow or create their own dynamics, tempo, and stylistic interpretations, whether explicitly written by the composer in the music or not. They decide what indicators such as espressivo, sehr langsam, sotto voce, or marcato mean, as well as how to follow the conductor, if there is one, and how to blend and collaborate with other members of the ensemble.

Performers are both expected and judged by how well they interpret what they see on the page, and what may not be indicated, including a myriad of interpretive factors usually referred to as “expression” that will vary from one performer to another and ultimately give them the ability to evoke an emotional response to their playing in the listening audience, their fellow musicians, and themselves. Similarly, the act of transcribing is not just one of applying rules and the mechanical reproduction of a score. It involves applying one’s sense of aesthetics in order to create something that reflects the beauty and emotional impact of the score on which it is based.

As mentioned in the introduction to this chapter, Kivy sums up the idea of what he calls a personal authenticity as “bearing the special stamp of personality that marks it out…the unique product of a unique individual…they are particularly valued for having: the qualities of personal style and originality” (Kivy 1995: 123). While I agree with these characteristics, when it comes to symphony orchestras, that description mostly applies to conductors and soloists, and not so much to the orchestra musicians themselves – even the principal players. In an essay I published called “The Rise of the Industrial Clarinetist,” I railed against the idea of orchestra musicians having any personal authenticity (or rare instances of it) (Drapkin 2013). In today’s orchestras that operate under a union contract, musicians are no longer selected directly by the conductor as they were at one time but filtered by a committee of other orchestra musicians. I theorized that this method led to the selection of bland musicians because if you play with too much personal authenticity, then some committee members or the conductor will not like it and not vote for you, and you won’t get hired.

Kivy devotes an entire chapter in his book Authenticities to the issue of personal authenticity to musical works. He concludes that “the artistic skill of performers, when they are exhibiting personal authenticity, is more like the compositional skill of arranging than like any other thing that I can think of: that performances, when they exhibit style and originality, are more like versions of musical works” (Kivy 1995: 135). I fully agree that arrangements, or more specifically transcribing – the term I use throughout this discussion – can be considered as versions of the notated score. Kivy shifts from performer to arranger by saying that, “the arranger must have an idea of how the work goes in order to make a credible version of it. He or she must, in other words, have an interpretation, be an interpreter. And that gives us just the result we were seeking for performance” (Kivy 1995: 137). Philosopher Susanne Langer describes the musical performer as the composer’s “confidant and his mouthpiece.” In deference to my painter friend, a classical performer is still limited to the notes that are given to them on the page, while transcribing can be done in an infinite number of ways (Langer 1978: 215). By its very definition – transcribing – the notes are going to change, and this is where the role of personal authenticity comes in.

Therefore, the goal that I seek with my transcribed works is to “have an idea of how the work goes in order to make a credible version of it” (Kivy 1995: 139). Where the goal of a performer “is to leave the indelible mark of personal style and (one hopes) personal originality” (Kivy 1995: 139), my goal is to transcribe the work and capture a credible version of it in the format I chose, using my intersubjective sense of aesthetics in transcription. I seek to capture a credible but new version of the original score, although how I do it will likely be different from how other people may transcribe a work. Here is an example again using the Nutcracker:

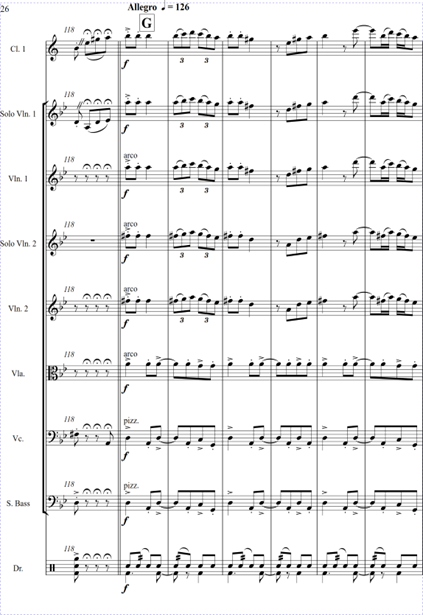

During the week of December 4, 2022, I performed in the pit for Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Ballet with the Venice Symphony in Florida using a version of the ballet score that was “orchestrated, edited, and arranged for the smaller orchestra” by John M. DeVries. It was selected because the Venice Symphony could not afford to pay for the full symphony orchestra instrumentation indicated in Tchaikovsky’s ballet score nor could the orchestra pit hold that number of musicians. This was performed with the following instrumentation:

4 – Violin 1

3 – Violin 2

2 – Viola

2 – Cello

1 – Bass

1 – Flute/Piccolo

1 – Oboe/English Horn

1 – Eb/Bb/A Clarinet (there is no Eb clarinet in the original score)

1 – Bb/A/Bass Clarinet (me)

1 – Bassoon

2 – Trumpet

2 – Horn

1 – Bass Trombone

1 – Timpani

1 – Percussion

1 – Harp

1 – Celeste/Synthesizer (for chorus)

26 musicians total, plus the orchestra was miked and amplified.

DeVries’ website touts that in his version “all important solos are scored for the original instrument” and “care is taken to preserve color and texture of the original composition” (DeVries 2012). This may have been DeVries’ intention, but the overwhelming opinion of many in the orchestra was quite negative to the point that after the performances both the Artistic Director and the Vice President of Artistic Operations approached me, asking me to create my version of the transcribed ballet. The issue of authenticity and aesthetics in transcribing a work takes on significant importance.

My book Extreme Transcription is devoted to the techniques, best practices, and principles that I derived and enumerated through the works that I transcribed. While transcribing can appear to be a sterile process or a set of rules, it is still a collection of aesthetic decisions that one makes. As seen in the previous paragraph, the ethereal and aesthetic nature of music remains a critical issue to the process of transcription, even though it is quite difficult to characterize, as pointed out by musicologist Daniel Chua and philosopher Lydia Goehr below.

Though speaking specifically about the fraught notion of “absolute music,” Chua’s work is situated at the intersection between music, philosophy and theology. He opines on the nature of absolute music in his book Absolute Music and the Construction of Meaning. Chua’s observations are equally relevant more broadly to this notion of what is or isn’t music:

What is this essence that so powerfully discriminates between what is and is not Music? There is no answer; or, at least, when asked to disclose the criteria for musical purity, absolute music deliberately draws a blank. Its signs signify nothing. Indeed, it cleverly champions this nothingness as its purity. The sign and referent cancel each other out in such a frictionless economy of exchange that no concept or object is left over. Thus, the meaning of absolute music resides in the fact that it has no meaning; the inchoate and the ineffable become synonymous. (Chua 1999: 4)

Goehr says something similar:

Musical works enjoy a very obscure mode of existence; they are ‘ontological mutants.’ Works cannot, in any straightforward sense, be physical, mental, or ideal objects. They do not exist as concrete, physical objects; they do not exist as private ideas existing in the mind of a composer, a performer, or a listener; neither do they exist in the eternally existing world of ideal, uncreated forms. They are not identical, furthermore, to any one of their performances. Performances take place in real time; their parts succeed one another. The temporal dimension of works is different; their parts exist simultaneously. Neither are works identical to their scores. There are properties of the former, say, expressive properties, which are not attributable to the latter. And if all copies of the score of a Beethoven Symphony are destroyed, the symphony itself does not thereby cease to exist, or so it has been argued. (Goehr 2002: 3)

I grappled with this issue of the nature and essence of music in what it meant to transcribe a musical work. In the case of the winds, brass, and percussion, I made the decision to cut down on the number of players in order to change these works from symphony size and accommodate the size of chamber orchestras while still including their instrumental timbres. For example, in the case of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, I made the decision to change the number of bassoonists from four to one, as I believed that I could retain the voice and timbre of the bassoon using just one player. Much of my transcription activities concerned these changes in headcount and my ability to retain what I considered to be the aesthetic nature of the original. These posed significant transcription challenges and I laid out how I responded to them in Extreme Transcription.

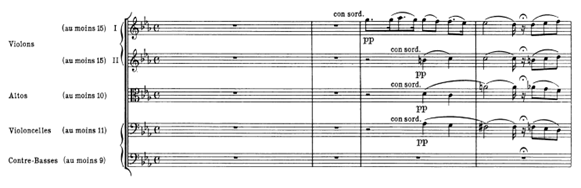

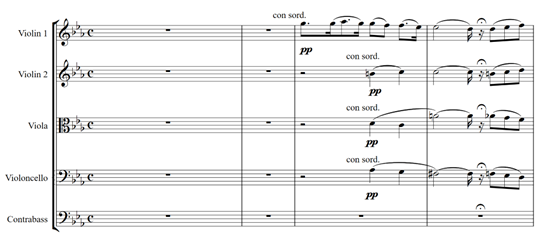

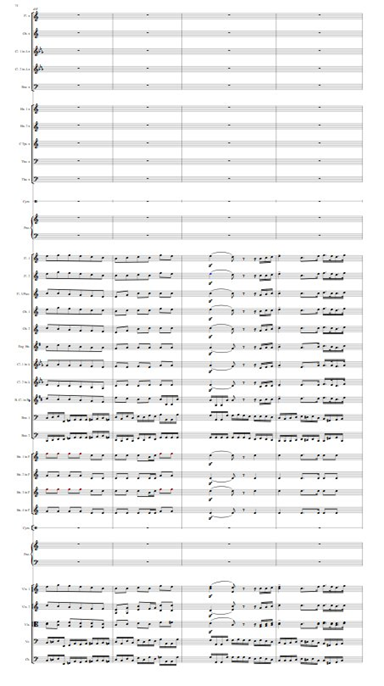

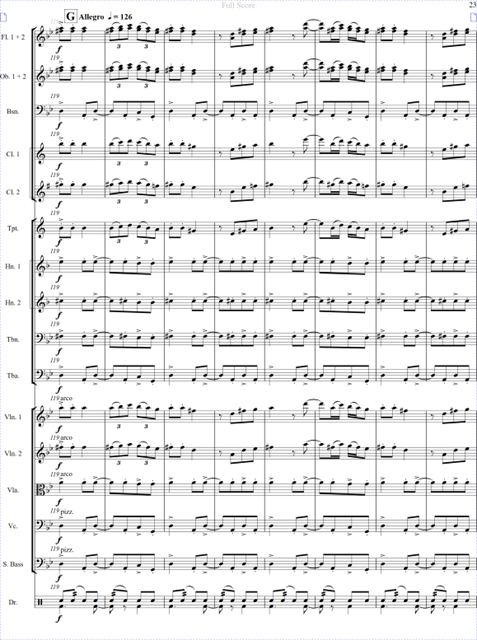

The string parts in my transcriptions require special examination given that the notes are largely left unchanged from the original. This begs the question of what the nature of transcription is in the case of the strings. The difference is (of course) in the number of string players in the orchestra. In a full symphony orchestra, there may be sixteen first violins, while in my transcribed chamber orchestra version there are four first violins, although the conductor may decide to change the number of string players.

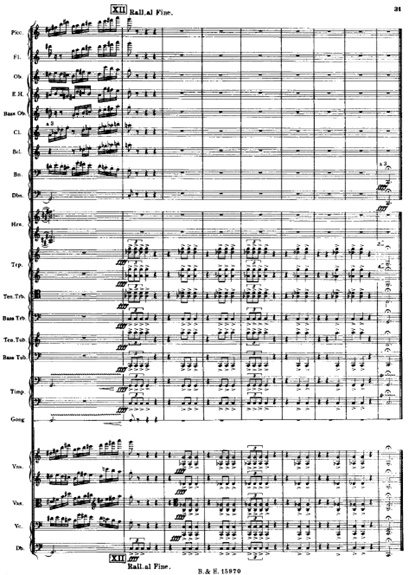

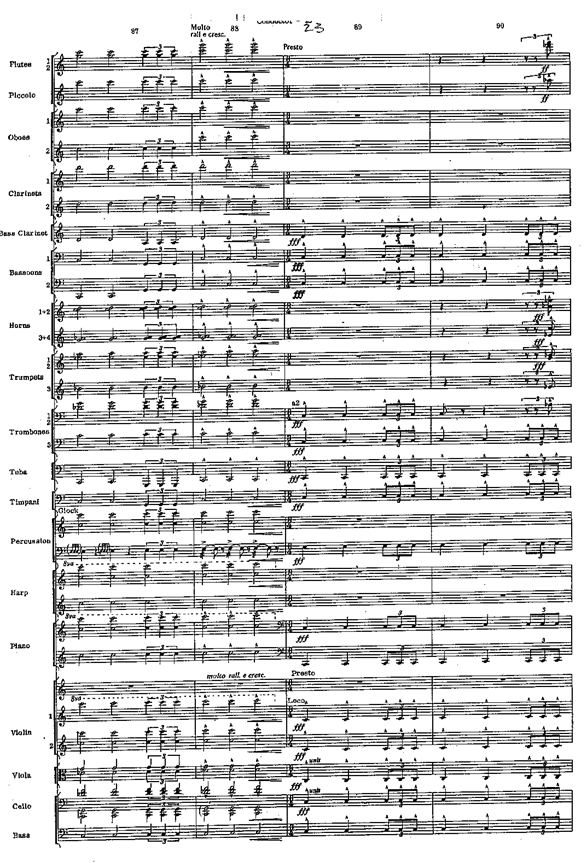

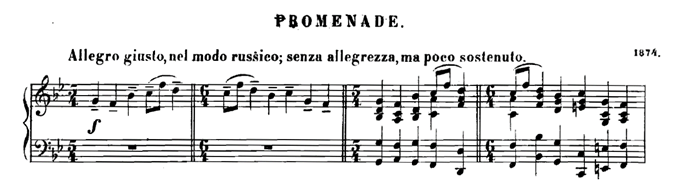

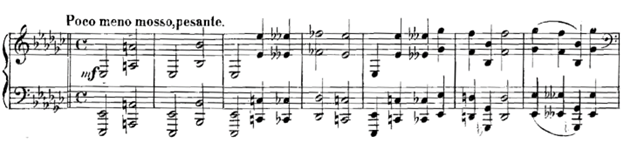

The difference between the transcription of the bassoon and the string parts is that it partly takes place outside the actual score, as can be seen in the two score examples and audio clips below. The cut in the strings doesn’t take place in the score; it takes place by specifying that the work is intended to be performed by chamber orchestra and not for symphony orchestra, which explicitly means less string players on each part.

Here is the original string opening in the first movement of Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique:

Figure 102: Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique Movement 1 Original Score. Bärenreiter -Verlag edition.

Audio: Figure 102 – Original work (Chicago Symphony) xb5.com/f144

Here is my transcribed string opening. It looks virtually identical to the original – but it is not. The score above calls for fifteen first violins, and in the recording below it is with four first violins (although since I left the amount of violins deliberately open, it could have been performed with 5, 6 or 2 violins as well). While the score may look identical, the difference in the number of violinists is significant. By definition, four first violins identifies this as a chamber orchestra, while fifteen first violinists identify it as a full symphony orchestra. Therefore, a big part of how the transcribed version can (or should) be performed cannot be seen in the notes of the score at all.

Figure 103: Transcribed Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique Movement 1

Audio: Figure 103 (Janáček Philharmonic Ostrava) xb5.com/f145

The basis for my personal authenticity in what constitutes the size and balance of the chamber orchestra is a result of the previous thinking I had done when cofounding the Texas Chamber Symphony in 2019. I argue that, from an aesthetic point of view, the orchestra can be limited to 22 musicians, including 4 violins (Violin 1 and 2), 2 violas, 2 celli and 1 contrabass. My goal was to have the smallest orchestra possible in order to make it cost effective since it was a brand new organization with very limited funding that we were trying to get started. But it was still paramount to me that it retain my ideas regarding aesthetics, balance, and timbre of the transcribed product. The instrumentation I used for Rimsky-Korsakov’s Capriccio Espagnol, which was the first work that I transcribed for chamber orchestra, is broken down by instrument: 23 players. Aesthetically I needed to add a harp, although my early draft of the score did not include it. Hence the orchestra size was increased to 23 players from my original 22. The last work I transcribed was Strauss’s Salome’s Dance. Here, I included a celeste on the basis of my aesthetic intuition; that increased the orchestra size to 24 players.

A big issue driving the number of strings is the balance between the winds and the strings, how the ratio of strings to winds changed over time, and how it relates to my aesthetics of transcription for chamber orchestra. While Chua and Goehr speak in general terms about the ontology of music, technical issues like the ratio of strings to winds and their effect on the balance and timbre of the orchestra is but one of the topics that comprise the aesthetics of transcription, or more specifically, my personal transcription aesthetic. These are the granular techniques that I specifically developed for the transcription process, the specific essential and practical implementation of aesthetic, ethical, cultural, and historically informed decisions that I necessarily have to make.

Regarding the historical sources that affect my transcription work, as Elliott Galkin points out in A History of Orchestral Conducting: In Theory and Practice, which includes Quantz’s observations on string ratios:

Quantz’s figures are significant: the proportions among the strings described in his smallest orchestra (4:1:1:1) [violin:viola:cello:bass] are the same as those which define their distribution in modern symphonic ensembles. We may infer from his instructions that as eighteenth-century groups increased in size, characteristics of instrumental balance were modified: emphasis was placed on the outer voices reinforced by the addition of woodwinds, the oboes doubling the upper parts and the bassoons the bass. Such polarity typified the Baroque Klangideal, and permitted the audibility of the keyboard instrument’s harmonic and rhythmic participation. This large proportion of woodwinds to strings is impressive. Recognizing Quantz’s specification of eleven woodwinds to twenty-one strings as reflecting the basic concept of orchestral sonority in the middle eighteenth century, we realize how dramatically instrumental balance has been modified during the past two hundred years: today the proportion of woodwinds to strings is one to eight, distributed throughout the entire tessitura of the orchestra. (Galkin 1989: 26)

Galkin’s observations regarding instrumental proportions exposes an underlying mechanism that drives the balance between winds and strings when it comes to reducing the number of players. This runs the risk of two things happening. First, the winds can end up overbalancing the strings to the point that the strings cannot be heard, especially when they have melody, and the loss of string timbre by using less players. This is the “audibility” mentioned in the above quote. The second issue is a difficult one that needs to be balanced delicately: what kind of string sound or orchestra sound do I want or am I willing to have based on the number of players? My intention in transcribing canonical works is for the timbres across the “tessitura of the orchestra” to be as familiar as possible, that is, as close as possible to the version of a full orchestra. I use the term “familiar” as I still want the work to be recognizable by the listener. It is much smaller, and significant changes have been made, based on what I could call, paraphrasing Kivy, my personal transcription authenticity. The decision over how many strings to use affects the string timbre, and that is an aesthetic issue that is decided outside the purview of the score. The smaller the number of strings used, the more transparent the sections may sound, to the point of hearing individual string players instead of the uniform string timbre commonly heard in larger orchestras. The opposite is to add more strings, which may deepen the string timbre, but increase the size of the orchestra, which may eventually take it out of the realm of chamber orchestra size.

The other solution to the issue of balance and timbre when diverging from the original score’s instrumental ratios is to reduce the number of winds and percussion to allow better ratios of winds to strings. The risk there is also losing voicing and harmony timbres in the winds by eliminating players. The aesthetic of the orchestra sound is thus either indicated by the score – which instruments and how many of them – or it can be determined by those that decide on how many strings to use, or both. In my case, I use what I believe is an optimal and viable configuration of winds/percussion and leave the specific number of strings to be determined by others, in the context of a chamber orchestra. Again, some aspects of the aesthetics end up being controlled inside and outside of the score. DeVries’ website indicates string minimums (3 1st Violin, 3 2nd Violin, 2 Viola, 2 Cello and 1 Double Bass), but that guideline may or may not be followed in practice. His solution to the issue of string:wind balance is to mike the strings (DeVries 2012). While I prefer to listen to this music unfettered by electronic amplification, there are cases where it is necessary. Miking an orchestra pit allows a smaller ensemble to be heard in a concert hall, and in the case of the Venice Performing Arts Center where I performed the Nutcracker, the pit is not big enough to accommodate the full symphony orchestration, so the use of amplification is not purely economic.

There are arguments both for and against this exercise in changing the original orchestration/instrumentation to accommodate the smaller size of the chamber orchestra. Said Goehr:

Instruments (notably the human voice), from the earliest times, were believed to be crucial to sustaining a religious and human conception of music. Of course, this information yields only a condition for something to be music: musical sounds must be produced by instruments. It does not motivate the condition that specific pieces of music have to be played on specific types of instruments. Precise instrumental specifications for individual works did become central to musical practice, however, as I pointed out earlier, in the late eighteenth century, concurrently with the so-called emancipation of instrumental music. Many composers at this time began to speak of instruments as ‘individual personalities with voices;’ many began to regard their specifications as unchangeable. (Goehr 2002: 59)

It is the unchangeability of instrumental specification or orchestration regarded by many composers as per Goehr above that is the central argument that could be made against transcribing symphonic works for chamber orchestra, even though that was freely done by many famous composers. But there is ample evidence for the opposite viewpoint. For example, New York Times critic John Rockwell examined the “deeply complex issue … about what constitutes music’s essence. Is it the abstract, formal structure of a piece, uncolored by formal trappings?” Rockwell concludes that some pieces, can “seemingly thrive under almost any sonic conditions” (Rockwell 1989). In a later review of a piano recital of Daniel Barenboim performing Bach’s Goldberg Variations, which were originally written for Baroque harpsichord, he comments, “it does reaffirm the ongoing place of interpretive divergence in our ever-evolving performance tradition” (Rockwell 1990). Rockwell has no problem with the Variations being performed on another instrument, and also comments, “nor does it mean one would now always wish to hear the ‘Goldbergs’ in the way and this way alone” (Rockwell 1990).

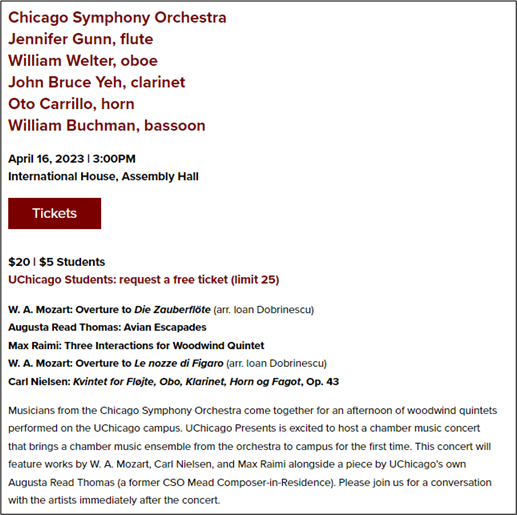

While Goehr states that in the late 18th century composers started to regard their instrumental specifications as fixed, and Rockwell refers to a constantly developing performance tradition, I would argue that there are implications to both statements with respect to the practice of transcription. Although many might object to the idea of changing the instrumentation, there is ample evidence that such a practice occurs commonly, even by the original composer. While the practice of changing instrumentation was common previous to the late 18th century, it has continued to present day and affords many smaller ensembles the opportunity to play works written for larger instrumental settings, which is one of my main arguments. What is evolving is the wider acceptance of the idea of changing the instrumentation. It is not unusual at all to see a transcribed work on a concert program nowadays. Note the following program for a concert at the University of Chicago with members of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Two of the five works are Mozart opera overtures transcribed for woodwind quintet:

Figure 104: University of Chicago presents a concert performed by Chicago Symphony members. Two of the five works are Mozart opera overtures transcribed for woodwind quintet.xb5.com/f142

And although Goehr notices a certain inflexibility among composers with regard to instrumentation, she too summarizes many arguments made for transcribing orchestral pieces, namely that they do not fundamentally change the core of these works:

But on further consideration we find a reason for thinking that instrumental specifications are not essential to works. If they are essential, how do we account for the belief that even though many works are transcribed or arranged for different combinations of instruments, subsequent performances are usually taken to be of the same work? Works may be altered in many different ways and yet arguably remain the same works. There are transcriptions – cases of music originally written, say, for the violin now performed on the clarinet. There are orchestrations – cases where composers orchestrate works of other composers. Schoenberg orchestrated Brahms’s Piano Quartet in G minor, Opus 25. There are also cases of composers orchestrating their own works. Schoenberg specified that his Verklärte Nacht be performed either by sextet or orchestra. Copland specified that his Appalachian Spring Suite be performed either by a small ensemble or full orchestra. Finally, there are arrangements, say, Busoni’s and Kreisler’s arrangements of music originally composed by Bach. Fritz Kreisler ‘composed’ almost exclusively by arrangement, or ‘in the style of.’ (Goehr 2002: 60)

I argue that transcribing for chamber orchestra is a form of Rockwell’s “interpretive divergence in our ever-evolving performance tradition.” And I certainly agree that there is a place for both the “original” and transcribed versions, as Goehr points out above. Peter Szendy, in his book Listen: A History of Our Ears, “testifies to a concept of arrangement as a means of transmission, as a method of communication of the original, for which it is substituted from then on” (Szendy 2008: 38). This is exactly the case with my transcriptions. The original score for symphony orchestra is scored for too many players to fit in the smaller instrumentation of a chamber orchestra (or orchestra pit), so it is substituted by the transcribed version in order to make new forms of communication possible.

I strongly agree with Szendy when seeking to preserve the music of the classical music canon and making them more widely available to audiences. The work being transcribed is still recognizable to the listener as “the same work,” even though the orchestration and ensemble size has changed. Taking the reworking of Beethoven symphonies by Franz Liszt as an example, Szendy strongly encapsulates the goal and responsibility that I seek and bear in transcription:

Liszt wrote, in his preface to his transcriptions of Beethoven’s symphonies (Rome, 1835): ‘I will be satisfied if I have accomplished the task of an intelligent engraver, the conscientious translator, who grasps the spirit of a work along with the letter.’ And again, this time speaking about his piano version of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique: ‘I scrupulously tried, as if it were a matter of translating a sacred text, to carry over to the piano, not only the musical framework of the symphony, but also the effects and the details.’ (Szendy 2008: 47-48)

Intelligent engraver, conscientious translator, grasper of the spirit of a work, sacred text translator, carrier of effects and details: transcriber. All of these roles come to bear when transcribing a work and the final version is the product of how I perceive these works. The changes I make in the process yield a new Klangideal, which is co-determined by my cultural, and musical background, as well as my aesthetic and ethical decisions. However, unlike Kivy’s description of personal authenticity as “the unique product of the individual” (Kivy 1995: 123), I don’t want the listener to think of my interpretation of the original work through the transcription process, or all of the granular aesthetic decisions and methodologies that I used, or of the inherent interrelationships between the original and transcribed work. Rather, I would prefer that they listen to a performance of my transcribed Symphonie Fantastique and forget that it was transcribed. I just want them to become enthralled and enraptured with Symphonie Fantastique.

These goals got muddied, however, as changes took place in the way that music was produced, distributed, and perceived, as well as the tools and processes that evolved to facilitate it. This will be explored in the next section.

3. How Technology Facilitates the Aesthetics of Transcription

Introduction

The technology used for transcribing music comprises the tools and methodologies used to take a composition from the brain of the transcriber and bring it to the ears of the listener. In my estimation, transcriptions, like other forms of composition, only truly exist when they are performed live. Until then, they are merely ideas in the transcriber’s head or dots on a page201. Technology has facilitated the inscription of a musical work from the earliest days of classical music202. While the tools available today on the computer cannot make someone a good composer or transcriber, they nonetheless can facilitate the enhancement of the aesthetics of transcriptions that lead towards the ultimate goal: live musical performance.

The technical implementations within notation software technology allow the transcriber to be more focused on the aesthetics of the transcription rather than on the time-consuming and labor-intensive tasks that were previously performed using pen and paper, although the old ways of writing music persist among some. They also maximize the abilities of the performing musicians in both rehearsal and performance by making their parts as clear as possible, thereby making efficient use of the group’s rehearsal time and greater accuracy during performance, thus enhancing the aesthetic impact of the performance.

Technology has provided new ways to make the transcription process more efficient and enables the ability to preview a work prior to hearing it performed by a physical orchestra. This is done by using synthesized and sampled sounds, providing notation editing capabilities that mimic modern word processing software, as well as minimize the labor intensive process of extracting parts from scores, among others203.

While the concept of technology facilitating the aesthetics of transcription might seem more practical than artistic, it is no different than an instrumentalist needing to practice scales and exercises in order to free themselves from technical boundaries in becoming a performing artist. The scales and exercises themselves are not aesthetic, but they provide the foundation that enables the artist to focus on the aesthetic qualities of their playing, such as expression and phrasing, in order for them to be able to communicate music in the best possible way to an audience. Music notation systems empower the transcriber with a powerful set of processes to set the music in their imagination down in concrete form quickly and efficiently and thereby help to facilitate it towards the ultimate goal of performance. Transcribers therefore can spend more time mulling over the aesthetics of their composition than the mechanics of music engraving. The tools in the software – editing, playback, part extraction, etc. – are the scales and exercises of transcription that free the transcriber to aesthetically create art. It is all part of a larger aesthetic continuum: from imagination, compilation, implementation, validation, transmission, to the live performance204.

Pre-Computer Music Composition Processes

Music Notation and Permanence

While this entire section is an examination of technology and transcription aesthetics, what preceded computer music notation systems is significant, given that they formed the basis for the processes and technology that were later implemented in computer software.

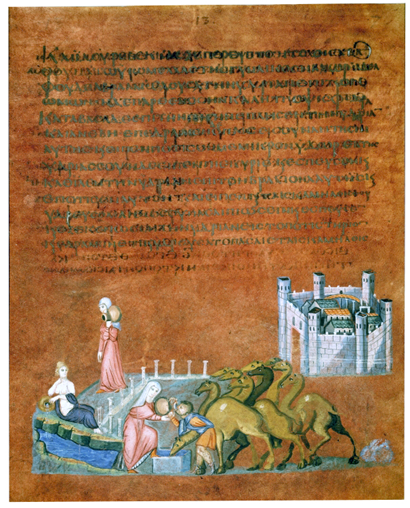

Figure 201: “Aimè che fai”, frottole for 4 voices, from a presentation songbook, c.1496. Modena, Bibltioteca Estense,it. 1221, fol.65v (Il Bulino)

Figure 201: “Aimè che fai”, frottole for 4 voices, from a presentation songbook, c.1496. Modena, Bibltioteca Estense,it. 1221, fol.65v (Il Bulino)

The older method of inscribing music was to use paper or vellum (in the medieval period) and a writing implement, such as a pencil or a pen (Tuppen: 2013). Engraving and notation techniques changed over time, as can be seen in the songbook example in Figure 201205. However, classical musicians still use Western music notation to encode and perform music, although some 20th-century composers extended the notation or invented their own notation (Hall).

The calligraphy of this Italian song (frattole) in Figure 201 uses an early notation system that is not fully understandable to most current classical musicians unless they study Medieval or Renaissance music206. But what is still recognizable are the familiar five line staff and noteheads, flags, and other symbology that survives today, and that make up the core of our current music notation systems as fully supported in computer music editing systems. Programs like Sibelius can support Renaissance mensural notation, but with some difficulty.

As in the painting in Figure 202 by French artist Nicola Turnier (1590 – 1638), early music notation systems changed music from an oral (sung) or aural (sung and instrumental) tradition in which songs were performed and passed on from one musician to another by ear, to achieving permanence: they could be passed on without relying on physical oral/aural methods. This was achieved by encoding music on paper using a notation system that enabled it to be passed to one or more performers with fewer modifications.

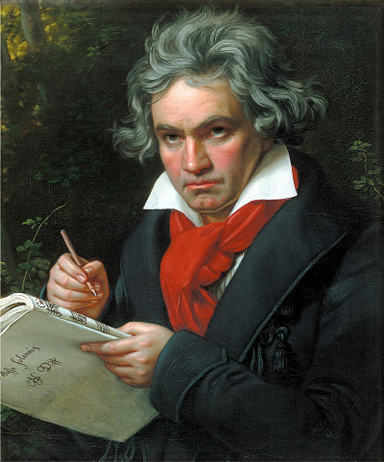

Something like this is suggested in the 1820 portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827) by Karl Joseph Stieler (1781 – 1859) in Figure 203, where he is apparently composing by encoding his musical thoughts using paper and pencil. This eliminated the need for performers to be physically present when music was being performed and transferred from one musician to another.

Thus, the frattole in Figure 201 lives on in written form today, whereas songs transferred via an oral tradition may change over time based on the interpretation of the performer or be lost altogether207. The permanence of written music lends itself directly to computer systems, which use data storage with which to retain and modify the information that it acts upon. Music notation systems share the data storage paradigm of the computer with the ability of software to create, edit, audit and retain music for distribution to performers.

Figure 202: Turnier, Nicola (1590-1638) A man with a lute.

Figure 203: Portrait (1820) of Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770 – 1827) composing using paper and pencil by Karl Joseph Stieler (1781 – 1859)

Handwritten Scores

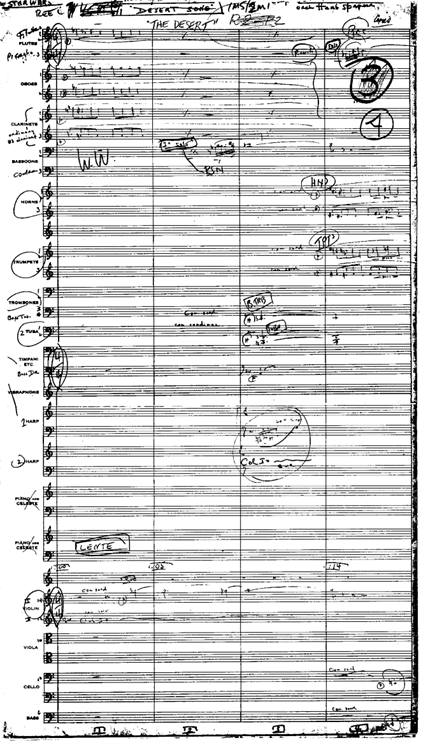

Handwritten scores like Weber’s in Figure 204 can be very difficult to read, and consequently very difficult to edit. With modern computer software, these difficulties are eased: once the score has been entered into a computer notation system, one has the ability to “cut and paste,” as can be done with word processing software. The method of writing a score by hand is very time consuming and does not lend itself to making changes or corrections easily. This can have an impact since the individual parts that make up ensemble or symphonic works are manually extracted and copied out by hand while maintaining note accuracy.

Figure 204: Hand written score for Act 2 of the opera Der Freischutz Op. 77 (1821) by Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826).

Figure 204: Hand written score for Act 2 of the opera Der Freischutz Op. 77 (1821) by Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826).

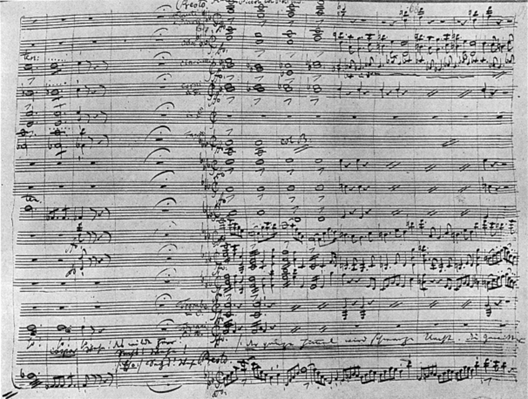

The Beethoven example in Figure 205 shows one of the limitations of writing music with pen and paper: it is difficult to make corrections or changes. This is very different from engraved editions of classical music. These were often created by publishing houses, so unless one was able to obtain a publishing agreement or was willing to hire a music copyist, the scores more likely than not would remain in the form shown in Figure 205. The advent of relatively inexpensive desktop computers and engraving software systems opened up and decentralized music publishing to the point that today anyone can create publishing-quality typeset editions208.

Figure 205: Crossed out score to String Quartet Op. 18 No. 1 (1792) by Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770 – 1827)

Figure 205: Crossed out score to String Quartet Op. 18 No. 1 (1792) by Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770 – 1827)

Attaining Audio Feedback During the Composition Process

Keyboard musical instruments date back to the 3rd century B.C. with the invention of the Ancient Greek hydraulis, which was an early type of pipe organ (Apel 1997: 9). Therefore, keyboards have been available to assist in the music writing process for millennia. The act of composing using a keyboard assisted many composers and allowed them to hear, verify and validate their conception of the harmony and voicing. See the portrait of Joseph Haydn (1732 – 1809) in Figure 206, apparently composing using quill pen, paper and keyboard.

Keyboards could not reproduce timbre or orchestration as they were not polytimbral, the exception being pipe organs with multiple manuals, each assigned to a different pipe rank timbre. The ability to physically hear what the composer heard in their head and saw on their scores using a keyboard allowed them to audibly verify at least part of what they were writing and imagining and gave them some sense of the aesthetic qualities of what they were writing. It also allowed them to improvise and create music using keyboard skills. The alternative was to get an orchestra together to read a symphonic composition.

Figure 206: Portrait of Joseph Haydn (1770s) by Ludwig Guttenbrunn (1750 – 1819) Haydn using quill pen, paper and keyboard.

The ability to attain audio feedback during the composition process was transformed in computer notation systems when they began to render the audio of scores for playback using sampled and synthesized sounds. The audio quality of the computer playback feature has evolved to the point that some listeners can’t tell the difference between a computer rendered orchestra recording and an actual orchestra recording209. But the sound being rendered by the computer is still ultimately a recording, and not the sound of a live orchestra. Nevertheless, it is still highly useful for gauging the aesthetic qualities of a work being entered into a computer notation system.

Figure 207: Elliott Carter (1908 – 2012) in 1960 composing with staff paper, pencil and keyboard (AP Photo/John Lent, File)

Figure 207: Elliott Carter (1908 – 2012) in 1960 composing with staff paper, pencil and keyboard (AP Photo/John Lent, File)

Many famous composers used the keyboard as part of their composition process, but not all, nor did they all adopt notation system technology. As Virgil Blackwell (Elliot Carter’s personal manager until the composer’s death in 2012) confided to me: “Elliott never used Sibelius or Finale, always the old pencil and paper just like John Williams210.”

The Elliot Carter photo in Figure 207 was taken 10-15 years before viable computer-based music engraving would start to emerge, and 28 years before the emergence of software like Sibelius.

Until the 1970’s, music was still written using staff paper, pencil or pen, and sometimes at the keyboard, and it was engraved for publication by hand using metal sheets and punches and knives, or newer mechanical devices such as a Music Typewriter (Figure 208)211. There were a number of music typewriters developed that were used for music engraving until they were supplanted by computer systems and printers.

Figure 208: Example of a staff created using a Music Typewriter. By the author, circa 1977.

Some writers of music eschew the use of computer systems for music engraving today, and probably will in the future based on their personal preferences and needs. In all likelihood, if they are to be published, these handwritten scores are given to a music copyist who transfers them into a computer notation system.

Enhancing the Aesthetic Qualities of Music using New Technology

Computer music notation emerged in the 1970’s when Stanford University’s Leland Smith created a notation engraving program named “Score” on large mainframes. Eventually it was ported to desktop computers using the MS-DOS operating system. Score created high-grade typeset-quality sheet music that was initially printed on a computer-controlled plotter and eventually could be printed on an attached laser printer. Smith’s system never made it to computer operating systems with graphical user interfaces such as Microsoft Windows, or Apple’s macOS212.

When computer music notation systems first emerged, they enhanced the music printing process, but did not provide aesthetic functions for composition. Two market leaders emerged for graphical music editing: Sibelius and Finale. Both provide visual music editing in PC/Windows and Apple/macOS workstations. Finale came out in 1988 and Sibelius in 1993, and they continue to improve with new features and regular releases, although Finale was pulled from the market by its owners.

Transcription Using Computer Notation Systems

Computer notation systems bring significant advantages, like cutting and pasting, automatic transposition and many other features (warnings about instrument ranges, etc.). These allow music to be written much more rapidly than manual scribing systems. More importantly, they also allow the transcriber to focus more on the aesthetic qualities of what they are writing than the time consuming and painstaking manual processes of writing notes onto paper by hand.

Notation Software Challenges

Software like Sibelius can be very powerful, but in many ways they are like purchasing a professional-grade camera. One may be able to use these very sophisticated pieces of technology, but they don’t give you an aesthetic eye for taking great photos. Having powerful notation software doesn’t necessarily make someone adept at making transcriptions.

For all of the sophistication of these notation software systems, they can’t stop someone from writing impractical or unplayable parts or poorly edited scores and parts. However, they do give warnings about parts written out of the known range of the underlying instrument.

Software programs can be arcane, highly complicated and difficult to use, which can make them less effective in practice. Because of their complexity, I have always felt that every time I undertook a new project using Sibelius software, I learned something new about how to solve a certain notation problem. Because of their complexity, it can be difficult to remember or figure out how to get programs to perform some of the tasks of which they are capable. Unlike musical instruments, which are built to specific standards (keys, strings, valves, etc.), software can have an enormous amount of functionality that can be expanded over time and can cross multiple genres. Some projects have specific requirements, for example when writing for jazz or choral ensembles. While the metaphor of learning scales on an instrument and learning how to use the software mentioned in the introduction to this section still holds, the use of support materials like compiled notes, software “help” sections, user groups where one can post questions – or even using Google to search for an answer – all buttress the basic ability to achieve one’s notation goals.

Notation systems require thorough knowledge of notation and engraving in order to create professional quality sheet music, and the systems are not great at certain functions, like finding usable page turns in the parts, or of formatting scores and parts. This is explored in the next section.

Achieving Value from Part Extraction

Extracting individual parts from a score is a powerful tool provided by notation systems. But getting them to create publication quality parts can be challenging. Part extraction is examined here as an example of how a very robust software function can require significant work and skills in order to derive benefit. It can also affect the aesthetic aspects of the transcription.

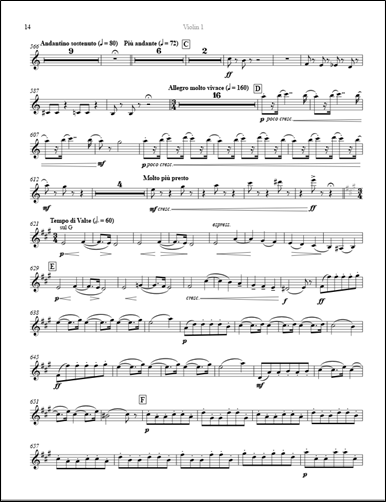

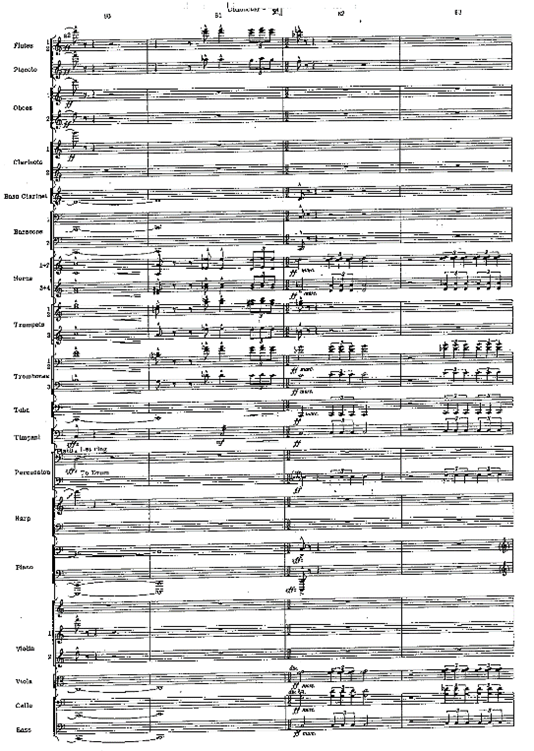

Figure 209 is an example of an instrumental part that the Sibelius notation system extracted from a score. In this case, it is the Violin 1 part to my transcription of Act I of Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Nutcracker Op. 71 (1892) for chamber orchestra. The formatting of parts can require complex skills in order to bring all of the parts up to professional engraving quality. Poorly formatted parts have a direct effect on the aesthetics of the transcription. If the parts are difficult to read and bad page turns interfere with their ability to play continuously, then performers will make more mistakes and take up time that could be spent focusing on other rehearsal-related issues, or aesthetic issues such as expression and interpretation. This can lower the quality of the final performance, since the amount of rehearsal time allotted for a performance is usually fixed. Therefore, poorly formatted parts can cause aesthetic aspects of a performance to be diminished.

Instrumentalists as well as the conductor can devalue the overall aesthetic worth of a work and won’t want to perform it because of poorly engraved parts in addition to a clumsy arrangement213. Instrumental part legibility, as well as a host of other seemingly technical notation issues, including wrong notes, can result in reduced aesthetic outcomes when performing a work, and can lead to it being replaced by another version, or not being performed. This is confirmed by John Wilson, conductor of the Sinfonia of London:

You’d be amazed at the difference good quality orchestral parts make to performance,” he said. “They can make it or break it. You can hit the ground running without having to decipher things. (Wilson in Morris 2023)

Note the raw form of this page in Figure 209, as initially created by Sibelius notation software, of a page of the violin part from my transcription of Act I of The Nutcracker. It is of very poor quality, the spacing and proportions make it difficult to read, and its use would result in serious complaints from the musicians.

Figure 209 An example of an unedited part extracted out of a score by Sibelius.

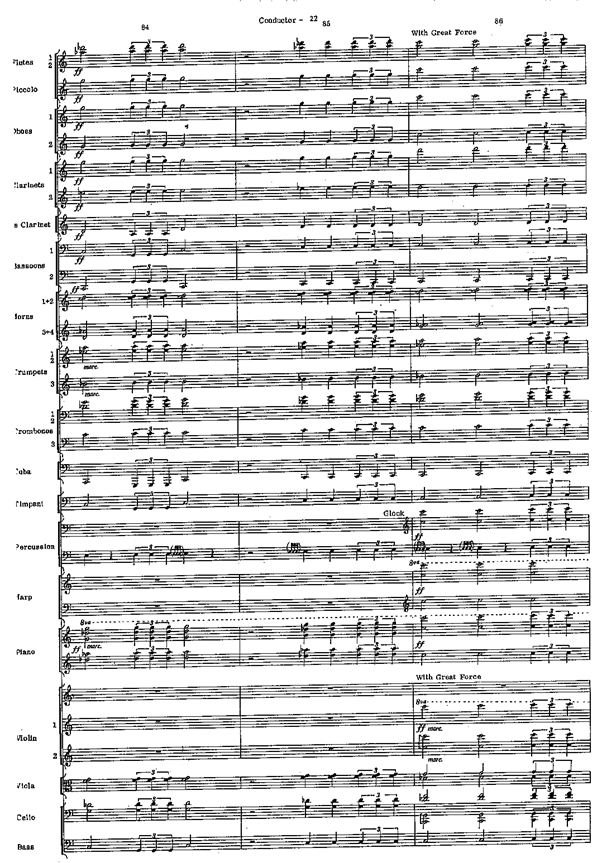

Figure 210 shows the same part after significant manual editing. Substantial notation skills are needed to reach this quality of engraving. This is the level of work that musicians expect to see. Anything less can potentially result in poorer aesthetic outcomes, and it might even result in the work being rejected by the performers outright.

Figure 210: Same part after significant manual editing.

The Value of Notation System Sound Rendering

Computer software allows one to use their ears in the process of transcription and validation and to hear renderings of works created using sampled and/or synthesized sounds. These can be added on to the notation systems and are quite realistic, ranging from the $129 NotePerformer to the $10,000 – 20,000 Vienna Symphonic Library (VSL). Such software addons offer many more possibilities for audio preview of a work before live performance takes place than composing at the piano provides the transcriber214.

It is useful to listen to computer playback using a high-end set of headphones as the fidelity can allow for more detailed listening. This gives one the possibility to hear a rendering or approximation of what the work is likely to sound like when performed, and whether that rendering matches what one had in mind. The higher the fidelity of the playback, the better one can judge the aesthetic aspects of the work.

It also allows errors such as wrong notes to be detected by listening to the playback. In this instance, validation is achieved by using the ears rather than being limited to looking at the sheet music with the eyes.

The playback capability of notation systems using add-ons like NotePerformer and VSL can create remarkable renderings of transcription scores, to the point that when I shared this audio with colleagues, they have remarked, “what orchestra is that?” The quality of the rendered audio can be extraordinary, especially when produced with high quality sampled sounds. Listen to these YouTube examples with high fidelity headphones, if possible:

First, here is how Rimsky-Korsakov may have composed his canonical orchestral showpiece Capriccio Espagnol at the piano:

#1: xb5.com/f169

As stated earlier, this gives one an idea of the notes, harmony and voicing but nothing about the orchestration or even an inkling of what the composer may have been intending it to sound like in performance. For example, you cannot tell that a clarinet solo starts in bar 17 by listening.

Next, Rimsky-Korsakov: Capriccio Espagnol transcribed for chamber orchestra by me, rendered by Sibelius using the NotePerformer plugin:

#2 xb5.com/f170

This was 100% produced by the Sibelius notation program on the computer as rendered by the NotePerformer addon using a combination of sampled and synthesized sounds. This gives a completely different perspective on the work and how it is orchestrated compared to the piano version above.

Finally, here is the exact same transcription performed by the Janacek Philharmonic Ostrava in a recording studio with audio engineering by Zarex Corporation:

#3 xb5.com/f171

The aesthetics and sonics of this recording are better than examples 1 and 2 above, but this required hiring a recording studio, a professional orchestra and a recording engineering firm to create the final product. While it is an outstanding recording, it is like Frankenstein’s monster: it was stitched together from a variety of takes and was recorded using multiple microphones. It also cost many thousands of dollars. The NotePerformer software that was used with Sibelius to create the audio in #2 costs $129 for a single use license, whereas the cost of recording with the Janacek Philharmonic Ostrava cost roughly $14,000, although their purposes are different: Sibelius/NotePerformer is a tool for transcribers and the Ostrava sessions were held in order to create a recording.

Third Party Copyists and Reviewers: The Internet and PDFs

Because of the geographical reach of the internet and standardized digital document formats like PDF, one can engage music copyists familiar with notation software to assist in the transcription process. They can live anywhere in the world and musical works can be near-instantly transmitted back and forth using email. Copyists in Nebraska and Kazakhstan are used to help with some of the labor-intensive aspects of transcription, such as entering an original score into Sibelius or proofreading. When the score to Strauss’s Salome’s Dance needed to be entered into Sibelius format, a music copyist in Nebraska was engaged to enter most of the score and he emailed back a Sibelius (.sib) file. These became musical assistants, much like the assistants that carried paint up and down the scaffolding when Michelangelo painted the Sistine Chapel (King 2003: 66).

Entering the original work into digital form is a prerequisite for transcribing works on the computer. Using a third party for entry allows for the transcriber to focus more on the aesthetics of the transcription. By using a third party professional that is an expert on score entry and proofreading, the transcription can be of higher quality and less prone to errors. In the worst case, an error in the original digital version may be carried over to the transcribed version215.

One can also extract all of the parts to a score, render it in PDF file format and email it out for review by the individual instrumentalists. This allows one to gather feedback on the transcription well ahead of any reading sessions or rehearsals, as well as catch errors that might take up rehearsal time or otherwise reduce the aesthetics of the work.

This could all still be achieved using pen and paper and the mail to send out parts for review, but that is impractical. Nowadays, orchestra players use email as a common practice for disseminating information, and PDF files for distributing digital copies of sheet music.

Notation System Best Practices

Today’s software notation systems bring capabilities to the transcriber that could only be dreamed about in the pre-computer days. Because of the complexity of these programs, they can be used in many different ways, enabling and enhancing the aesthetics of the transcription. In my experience, I have found that certain software functions like “Optimize Selection” and “Reset Note Spacing” to be critical to making the formatting process more efficient, thereby freeing up time for the transcriber to focus on the aesthetic qualities of the transcription.

Here are some methodologies developed to enhance the process of transcription and improve the aesthetics of the resulting work:

Modeling Orchestration Within a Notation System

One method that can be used when evaluating the aesthetics of a section is to highlight the staves that are being considered for use in the transcribed version and having the software selectively play them back. This way one can model and evaluate the aesthetic nature of what the transcribed section will sound like before committing to the changes. See Figure 211.

Figure 211: Aesthetic modeling by selecting voices (in blue) to play back.

Visual Transcription (Old at the Bottom, New at the Top)

Another method is to put the new staves of the transcription at the top and old staves of the original score at the bottom. Thus, part of the process of transcription can be a matter of methodical cut and paste. One is not limited to the size of the virtual staff paper within the notation program and can change it to any size. Therefore, in the example in Figure 212, the size of the page is set to 10” x 18” so that all of the staves can be comfortably seen on one page216.

With so many staves on the page, one can easily become disoriented and make mistakes, lowering the aesthetic quality of the performance. This technique of resetting the page size allows one to keep track of where one is working on the page and improves the ability to take the ideas in the transcriber’s head and translate them into their conception of a transcribed page of music. Others may do this differently, but my method has proven to be an effective way to manage the transcription when dealing with many staves.

Also, because there are so many staves on the page in music scored for a large orchestra, another technique is to mark the name of the target transcribed parts with an “x” at the end, such as “Fl x.” Since there are staves for flute in the original score, it is easy to get confused as to what the transcriber is focusing on: are they the new staves or the old staves? This way they are visually differentiated. Again, it allows one to keep track of what is actually being worked on so that the focus can be on the aesthetic result: how it sounds when it is performed. See Figure 213.

While these techniques may seem more like organizational than aesthetic processes, they are highly important as the overall process of transcription can be very complex, especially when dealing with a large score like The Nutcracker, which is over 500 pages long and is scored for a large symphony orchestra. The techniques proposed here help to minimize this complexity and aid the transcriber in focusing more on the aesthetic qualities of the transcribed score, which ultimately affects how the performance will sound. These are not the only techniques available in assisting the transcription process (as they are numerous), but they give an idea of how these systems help facilitate and minimize the mechanical processes so that the focus remains on the aesthetical aspects of transcribing. These are large differentiating factors between the manual processes of yesterday, and the technological processes of today.

Figure 212: Extended score showing both old and new voices.

Figure 213: Distinguishing between old voices and new voices.

Conclusions

Music technology evolved over time to help facilitate the aesthetics of transcription. It now provides powerful computer tools that enable people who write and engrave music to create, edit, validate and listen to the work that they create prior to it being physically played. The software is highly complex and requires skill in order to produce publication-quality sheet music.

Putting music to paper gave compositions permanence where they would have otherwise been lost or changed when passed by ear from one person to another. Moreover, it formed the basis for the processes and technologies that were later implemented in computer software notation systems.

Handwritten scores can be very difficult to read and edit once they are put down on paper using ink, and in the case of instrumental scores the individual parts need to be manually extracted, which can introduce errors. This was overcome when a publishing agreement was obtained or if a music copyist was hired, unless the composer himself had the time, inclination and skills to create engraving-quality manuscripts.

Keyboards were used by many writers of music as part of their compositional process, as it allowed them to physically hear the music that was in their head. But since these instruments are not polytimbral (except for organs), they do not provide aural feedback for orchestrations that use multiple instruments. This limitation has now been overcome by computer notation systems, which can provide renderings of works that have been created with their software using synthesized and/or sampled sounds. It also provides for error checking and validation using the ears in addition to the eyes.

Computer music notation software emerged in the 1970s and have evolved into relatively inexpensive systems that enable desktop music publishing, which was previously mostly the purview of publishing companies. This software notation technology gives the transcriber some powerful tools with which to facilitate the transcription process and reduce what were previously some very time consuming manual processes.

The functionality in these systems can greatly enhance the aesthetic processes of transcription (as well as increase productivity). Some examples of this are part extraction, audio preview and sound rendering, and the ability to integrate the use of third parties and reviewers by transferring music digitally using the internet, email and PDF files. There are also many best practices that can be learned and developed that can enhance the writing process such as orchestration modelling and visual transcription.

Given the complexity of today’s notation software, the effect of technology on the aesthetics of transcription may be more directly related to a person’s skills at operating those programs than their own sense of aesthetics. But it has given writers some very powerful tools that, when used effectively, can enhance the aesthetics of the works that they create as well as enable the publication and distribution of their music by individuals in ways that were previously limited to corporations.

But all of this digital technology has also opened the way for ethical issues, which will be discussed in the next section.

4. The Ethics of Music Attribution

This section examines how changes in musical production processes, technology, and media have affected our understanding of some of the ethical issues associated with the attribution of credit to those who contribute to the making of a musical work, either transcription or other musical forms.

Introduction

The evolution of how music is created in our current era, replete with computers and software, raises questions about who actually authored a musical work. Lydia Goehr has posited that the concept of attribution has a long history that only began to be clarified around 1800. Prior to that time, there was little regulation of what constituted a work, or what Goehr has referred to as a “work-concept”:

“We need to distinguish two potentially distinct claims: first, prior to 1800, the work-concept existed implicitly within musical practice; second, prior to 1800, the work-concept did not regulate practice.” (Goehr 2002:114)

Before that period, there was little or no concept of music as intellectual property, especially since composers were in the employ of rich patrons or religious institutions. In other words, works were presented for entertainment, sacred or incidental music. There was no concept of the concert hall for the formal presentation of music yet. (Goehr 2002:115) It was not until after 1800 that composers such as Berlioz and Liszt began to control and identify their works as their own. Prior to that time, composers freely used materials from other composers, or themselves, or in the case of opera scores – final adjustments to the music were commonly made at or before performances by others301. This likely is what has made the cataloguing of works by Wolfgang Schmieder (1901 – 1990) of J.S. Bach’s (1685 – 1750) works and Ludwig von Köchel (1800 – 1877) of Mozart’s (1756 – 1791) works such a challenge – applying rules developed later to works prior to that period. This is summed up by Goehr:

This way depends upon our importing a conceptual understanding given to us when the work-concept began to regulate practice. Just as a piece of pottery or a pile of bricks can come to be thought of as, or transfigured into, a work of art through the importation of the relevant concepts, so, since about 1800, it has been the rule to speak of early music anachronistically; to retroactively impose upon this music concepts developed at a later point in the history of music. Implicit existence has become here essentially a matter of retroactive attribution (Goehr 2002:115).

While the attribution of a work became clearer after 1800 by composers assigning opus numbers to their own works, the practice of using musical materials from other composers continued through explicit transcription302.

The complexities associated with attribution continue to this day. As we will see below, there are cases where a work is represented as having been created by a single individual when in fact there were more people fundamentally involved in its creation. It also raises the question of attribution in my own transcriptions. Did the person identified as the composer actually write the work? Did I? Consider the following: